With the arrival of Rolling Stone Philippines in the country, it seems that we’re starting to see an uptick of investments into the media side of the music industry. The return of Billboard Philippines last year, the launch of their charts, numerous concerts, and the dominance of original Filipino music in the mainstream are all signs that point towards a strong demand for platforms that champion Filipino music.

Having not just one, but two international music publications in the country is a feat in and of itself, especially considering that our music market is a blip relative to the rest of the world. However, when the two legacy media names are operated by the same holdings company, the question arises: for whom are these media brands in service of?

The mighty pen

It seems like over the past couple of years, corporate-backed music journalism has taken a huge hit. Condé Nast’s Pitchfork had their editorial staff gutted, and then folded into GQ. Both NME Asia and HipHopDX Asia downsized and were folded into their respective parent brands. The loss of NME Asia and HipHopDX Asia were tough blows for the Asian music community. These platforms offered in-depth and exclusive coverage for Asian artists in a way that their Western counterparts couldn’t.

Why does this matter? On the artist end, having press coverage (like features or placements on lists) can have direct effects on your career — whether it’s serving as additional promotion for your releases or providing support to help you book gigs and festivals.

On the other hand, music publications are still a part of the media. That means that they hold the same power that other mass media outlets have: to shape narratives. The media determines whose stories are worth telling, and what issues are important.

However, when corporate media outlets are continually chasing profits, their coverage will always be in service of the cultural and class elite. There is no in between. For example, in the context of entertainment media, who gets coverage is often determined by who can bring in the most page views. Page views are almost always the biggest factor for a publication to earn profit; the higher the page views, the higher chance of attracting advertisers, and so on and so forth.

So, if you’re wondering why mass music publications seem to only ever be covering artists with large followings or millions of streams…that’s the reason why. Now, if you apply that reality into an ethnically and linguistically diverse country like the Philippines, the problem gets a bit more complicated. It’s not just a battle between the independent and mainstream — it’s a battle between the elite and the working class. And it sure as hell is a battle between the ethnolinguistic majority (Tagalog) and the rest of us.

Imperial Manila strikes again

It’s no secret that there’s a deep cultural divide between “Imperial Manila” (and those who speak Tagalog) and those who are from Visayas and Mindanao (shortened as VisMin). This regionalism manifests itself in different aspects of Filipino society: government funding, infrastructure, development, and more. A 2020 study found that “provinces farther away from Manila in terms of geodesic distance are indeed disadvantaged not only in terms of economic, poverty, and human development indicators, but also in terms of dependence on internal revenue allotments which inhibits local growth.”

Regionalism isn’t just an economic and development issue. It’s a cultural one. It’s an open secret among VisMin music communities that there’s always been this pressure to move to Manila if you want to “be successful” in music. Major music labels will sign artists from the southern regions of the Philippines but still push these artists to relocate to Manila in order to make it big. You also have the fact that mainstream artists who were born and raised in VisMin — and mind you, a majority of provinces from this region rarely speak Tagalog on a daily basis — write and perform songs in Tagalog to seemingly appeal to a mass audience.

These instances are just a few examples of how regionalism runs deep in the country’s music industry. If popularity and streams are a deciding factor for press coverage, then Bisaya music and Bisaya artists will always be systematically disadvantaged in the country’s music industry.

We’re cultural and linguistic minorities, which means that we will never have the same number of streams and followers as a Tagalog-speaking, Metro Manila-based artist. On top of that, with the Philippine music industry being centralized in Metro Manila (major music labels, awards shows, and publications), we are also physically disadvantaged and excluded from the rest of the country’s music network.

All of this means that when publications are using metrics such as streams and followers to determine who gets press coverage, they are not acknowledging the social inequalities surrounding those numbers. It’s the same philosophy that guides the concepts of intersectional justice in human rights and other advocacies. Just as you can’t separate class, race, gender, and religion from how people experience the world, you cannot separate music from its political realities.

Can corporate media outlets ever truly invest in equitable journalism? I’m inclined to say no. At the end of the day, these big names media brands are businesses, and they need to prioritize profit over people. Sure, maybe a VisMin artist will get a featurette here or an article there, but it will never be truly inclusive of the many sonically and culturally diverse scenes in the southern regions of the Philippines.

Music as community

Despite, and in spite of those realities, all is not lost. While corporate media will continue to be ruled by profit, there is a rising crop of independent music media in VisMin that are motivated by genuine care for their local music communities; where music media is a form of community-building and not a business venture.

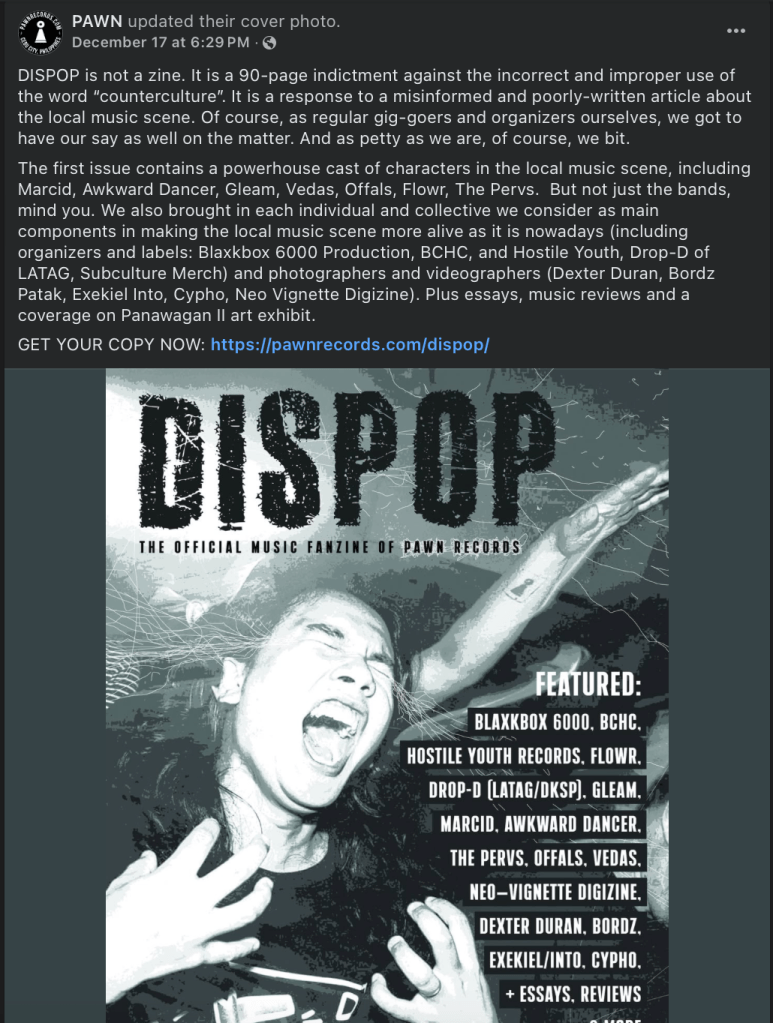

Take for example Cebu’s Lokal Sound Daily and its sister publication, Ecstascene in Cagayan de Oro, two social media publications that publish news on local gigs, local artists, and local releases in their respective cities. On the other hand, you have Scenes and Music Press, a multimedia platform helmed by musician-journalist Sam Salingay, that features video interviews with Bisaya musicians. Cebuano independent record label PAWN Records also recently launched DISPOP, a 90-page physical music zine featuring the musicians, creatives, and collectives that make up parts of the VisMin music community.

Independent media, especially those created by and for minority groups, are platforms where we can tell our stories in our own words. They’re platforms where we take collective ownership of the power of narratives. They function as community spaces that support VisMin artistry, regardless of how many followers you have, or how popular your music is. Due to the fact that profit is not the sole purpose for their existence, you’re able to get press coverage that’s arguably a better representation of the diverse music of these regions than you’re ever gonna get from a mass media publication. These platforms, whether physical or online, are community platforms. They are active spaces where art is something that is in service of the community; not in service of an individual, and definitely not in service of profit.

Because whether corporations like it or not; art, music, and culture can never truly be bought. It can never be truly, fully commodified. Art and music will always belong to the people — to communities.

My hope is that we continue seeing more independent music media from provinces in VisMin prop up. In fact, if you look at our Southeast Asian neighbors, the Philippines is behind when it comes to a whole network of independent blogs and publications. Countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore have a wide variety of publications that are dedicated to independent music scenes. A healthy ecosystem of independent, grassroots publications ensure that counter-narratives, subversive stories, and unique coverage are all still accessible despite the presence of mainstream music media.

It is now, more than ever, that we all rally to tell our stories on our own terms. In our own voices. Follow and support your local independent music publications. Reshare their content. Click on their websites and read the articles. Buy the physical zines. All of these actions show proof that our community is not as niche as people think we are. We’re here, our stories matter, and if no one’s going to tell them, then we’ll do it ourselves.